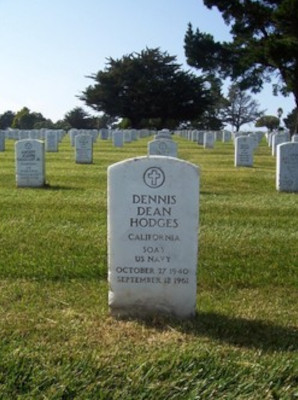

SOA3 Dennis D. Hodges

27 October 1940 - 18 September 1961

Navy Hymn

Dennis Hodges is buried in the Golden Gate National Cemetery, San Bruno,CA.

Picture taken in Olongopo, PI, during HS-6’s 1961 WESTPAC that Dennis Hodges sent home to his sister Kandi Hodges Adams.

Read the memorial page created by Kandi Hodges Adams.

Excerpt from “THE SAGA OF HS-6″ by Captain Terry M. Badger, USNR/Retired

The days at sea were, like the first cruise, agonizing. The time crept by ever so slowly. Everyone wanted to get home! We played cards, we paced the deck, we inventoried all our goodies, we had late night bull sessions, we watched endless movies – anything to make the time pass faster.

Finally, on September 18, the early morning departure from the ship came. We were sitting in our ready room, flight-suited up and ready to go. We had 14 birds up, so 28 pilots and 28 crew-men would be leaving the ship for the fly-in to Ream. It was foggy, but the visibility was above minimums, so we would be able to fly VFR to the beach. Earl Weinman was my 2P, and we were really excited to get in the aircraft and GO HOME! Finally, the famous and much anticipated word came: “Pilots, man your planes.” Since we had 14 birds to fly in, we were divided into two groups, as the flight deck only had 10 “rings,” or take-off spots. We would fly in in two flights of seven helos each, which was more symmetrical than two groups of ten and four helos. We knew the families would be waiting anxiously at the squadron spaces and we wanted to make the fly-in impressive. Earl and I were in the first launch, and were the 6th plane to lift off. We were to fly individually to the beach and then join up in a tight right echelon and head east down the Tijuana River and break smartly left over the end of the runway, make a 180-degree approach and land in front of the cheering throng that we envisioned awaited us in the squadron spaces. We could hardly wait. After takeoff, I made a slow turn toward the beach and called the ship to say, “inbound to Ream.“ There was little traffic on the radio, and the visibility was so poor we could not see another helo. This didn’t worry us though, as the fog bank off Imperial Beach was notorious for ending at the beach, and the air east of the beach would be crystal clear. We figured it would take us about 10 minutes to get to the strand, so we sat back, set the barometric altimeter for 500 feet and headed east at 80 knots. That’s when the call came.

“Wildcat, Indian Gal 51, over.” “Indian Gal 51, Wildcat, go.” “Wildcat, Indian Gal 51. I have an emergency. My throttle is hard over full and I can’t reduce it. I can gain altitude to keep the turns under control or I can gain airspeed to do the same. I am planning to do a straight-in to runway 9, cut the mixture and make a high speed autorotation. Crossing the beach now, feet dry.” We were all in a state of shock. The pilot was Earl Baker, an experienced pilot and a squadron test pilot. Of the six other planes in the air and the ship’s air controller, no one had the presence of mind to suggest, “Turn off the aux servo” This would have taken the throttle from automatic, servo-controlled mode to the manual mode which would have made it controllable. Earl, as an experienced HSS-l/1N test pilot, should have thought of it, but didn’t. Tragically, that omission would cost Earl, 2P Mike Fox and the two crewmen their lives. After Earl’s “feet dry” transmission, no one said anything. The radio frequency was silent until about a minute after Earl crossed the beach, a low voice said, “oh shit.”

“Indian Gal flight, Indian Gal 56. This is the skipper. Just passed over Indian Gal 51. Only thing visible is the helo’s tail sticking out of the mud. We will continue on to Ream as planned. Will notify Ream tower on Guard. Join up over the river mouth. Acknowledge.” The remaining five aircraft acknowledged. We had crossed over the beach during the skipper’s transmission, and as I made a climbing right turn to join up, we passed the helo tail sticking out of the swamp which covered the half mile interval between the beach

sand and the start of runway 9 at Ream. The tail was about halfway between the beach and the runway. God, I thought, what the hell happened? We joined up in right echelon and flew down the river and broke left into our landing pattern. As we headed west to land in the designated squadron spaces, we could see the large crowd gathered and the banners displayed with “WELCOME HOME HS-6” all over. I couldn’t help but wonder what the rest of the day would be like. Talk about bitter/sweet!

We landed and made our way through the crowd in search of our wives. Before I found Lynn (my wife), Earl Baker’s wife found me. “Where‘s Earl?” she asked, thinking he might be on the second flight in. “I think you’d better see the Skipper,” I said, not wanting to tell her what I knew would be the worst thing she would ever hear….

No one could explain what happened to Earl’s helo. The Sikorsky test pilot came out and in numerous flights (at altitude) tried to simulate the accident conditions, but was never able to get the helo to do what Earl’s apparently did. The skipper flew co-pilot on all those flights, which truly endeared him to all of us. It took real guts to do that! The conjecture was that when Earl cut the mixture, he didn’t get the collective down fast enough and the leading edge of the rotor blade on the retreating (left) side stalled, thus causing the helo to pitch up and roll to the left as the retreating blades lost their lift. This could never be demonstrated, so what really happened remains a mystery, even today.